Replacing or upgrading your home’s HVAC system? Consider a heat pump. Sometimes called mini-splits, the world is moving toward these electric-powered, super-efficient, all-in-one heating and cooling systems. Need a new air conditioner? It’s a no-brainer: Pick a heat pump instead. Need to add HVAC to a room or two? Mini-split heat pumps are the obvious choice. Replacing your heating system? Yep, a heat pump can work, and will even save some people a bunch of money.

Heat pumps have been common in warm parts of the US for decades, and advances in the technology mean they can now work year-round even in the coldest parts of the country. Since they’re so energy-efficient and environmentally friendly, some of the top models are now eligible for big government rebates and incentives.

Read on for a primer on heat pumps, and how to decide whether one will be a good fit for your home: What they cost, how they work, who can get one, how to find the right model for your home and local climate—and even when they might not be your best bet.

Did you know?

- Thanks to their clean energy credentials, heat pumps can be eligible for thousands of dollars in rebates and tax credits.

- Need a new air conditioner? Get a heat pump. In cooling mode, they work just like traditional ACs. Ductless mini-splits are a great way to get permanent cooling into a house with no ducts. The super-efficient heat is almost like a bonus.

- Ditching oil, propane, or electric-resistance heat for a heat pump will almost always save money—up to $1,000 per year according to the DOE, depending on local energy prices. It can beat natural gas, sometimes.

- Modern heat pumps can work in temps well below 0 degrees F. Not all heat pumps can handle these bitter temps, but plenty of them can.

- Heat pumps and solar power are a fantastic match. With enough solar panels, you can completely wipe out your heating and cooling bills.

- EnergySage makes it easy to find vetted, trusted heat pump and solar installers through our marketplace.

Who is EnergySage, and what do we know about heat pumps?

EnergySage has been bringing transparency to clean energy technology since 2009 after our founder Vikram Aggarwal spent months gathering quotes from dozens of installers. With funding from the Department of Energy’s SunShot Awards, we opened the country’s first (and now the largest) marketplace for rooftop solar panel installations, where vetted contractors compete for your business by offering quotes through our online platform.

Over the years we’ve added similar marketplaces for battery storage, community solar, and—most recently—heat pumps. We want to foster a healthy, transparent marketplace for heat pumps and other clean-energy upgrades, and that starts with educated buyers.

For this guide—and all of our related guides to heat pumps—we have:

- Examined more than 200 heat pumps: Their specs, cold-weather performance, and more.

- Analyzed dozens of real-world heat pump price quotes from vetted installers in our heat pump marketplace, as well as hundreds of additional price estimates from additional sources, including government offices, home services websites, and trusted editorial outlets.

- Found wholesale prices for a few dozen popular heat pumps (though the prices weren’t publicly available for all brands).

- Run a survey of attitudes among potential heat pump owners.

- Spoken to experts from around the HVAC industry.

Personally: I have more than a decade of experience writing about and recommending major home appliances and HVAC equipment, including stints at The New York Times’ Wirecutter and Consumer Reports. I’ve also made a bunch of progress electrifying my 100-year-old house outside of Boston. So far I’ve added an EV charger, an induction stove (replacing gas), blown-in cellulose insulation, and a rooftop solar system (through the EnergySage marketplace before I worked here). No heat pump yet, but it’s on the list.

3 things you need to know about your house

You’ll get more out of this guide—a better sense of your pros, cons, and options—when you know the following things about your home:

- What heating fuel do you currently use? It’s probably natural gas—according to the EIA, that’s the main fuel in about 50% of homes. Electric resistance is the next most common heating system. It could also be propane, oil, or wood. Knowing this answer can help you figure out how much money you might (or might not) save by switching to a heat pump.

- Does your home have ducts, and do they reach every room? If you see a bunch of air vents around your house, you have ductwork, and you’ll probably want to use it for a heat pump. If you don’t have ducts, or the ducts don’t do a good job in certain parts of the house, you could consider ductless heat pumps, which are easy to install. You can use a mix of both types, too.

- What climate zone do you live in? Check it on this map. Focus on the number, from 1 (Miami) through 8 (northern Alaska). This will help you narrow down the models of heat pumps that make sense for your home, based on how well they perform in the coldest temperatures you’re likely to get in your town. You could also look up your design temperatures by zip code—about 99% of the time, the weather will be in between the high and low design temps, and that’s the target that HVAC engineers design around.

)

What’s a heat pump—and why did everyone just start talking about them?

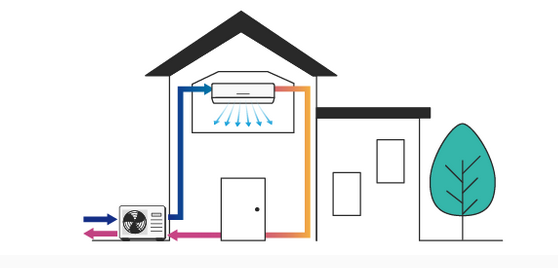

A heat pump is an all-in-one home heating and cooling system. We cover how they work in depth in another article, but here’s the short version:

A heat pump is sort of like a combined furnace and air conditioner, though it’s more precise to think of it like an air conditioner that can run backward.

In cooling mode, it absorbs heat from your warm, stuffy house and dumps it outside—exactly like a traditional AC does, using all the same components and tricks of physics. It reduces humidity, too.

In heating mode, it runs in reverse. It soaks up free heat from outside your home (even when it’s really cold outside), and moves it indoors.

This process uses less than half the energy of a traditional heating system, though it’s often even more efficient than that. The specifics depend on the heat pump model and how well it’s installed. Those energy savings often translate into significant cash savings, depending on what kind of heating system you’d be replacing.

Heat pumps are incredibly flexible:

- You can use them to heat and cool your entire house, or just one room, or some rooms but not others.

- They can be installed in nearly any single-family house and many townhouses, condos, and apartments.

- They work with ducts, without ducts, and sometimes even with hot-water radiators (though these are rare in the US).

- You can use a heat pump with or without a backup system—it’s a matter of personal choice in the vast majority of the country.

A bit of history: Basic heat pumps have been around for decades. About a quarter of all households in the southern US already use a heat pump as their main heating and cooling system, according to the EIA. The warm climate in that region is a natural fit for these systems.

The technology has improved by leaps and bounds in the past couple of decades (since the last time most people had to update their HVAC systems). Heat pumps that work well in colder climates began to appear in the US about a decade ago, following a jump in prices for heating oil. Today, there are plenty of models that work perfectly well in extremely cold weather—well below 0 degrees F.

Some contractors still insist that heat pumps don’t work when the temperature drops below freezing. They’re misinformed. Heat pumps are more common in some of the world’s coldest countries. Half of all households in frosty Finland now rely on heat pumps, for example.

As of 2023, interest in heat pumps has reached an all-time high in the US because the federal government and several states now offer huge incentives for installing them. It’s part of the effort to reduce carbon emissions, and heat pumps can make a huge difference on that front. That’s true even when they run on electricity that comes mostly from fossil fuels because they’re so energy efficient. The positive environmental impact is similar to driving an electric vehicle instead of a gasoline-powered car or switching to solar power. The cleaner your electricity, the greater the environmental benefits of a heat pump.

Heat pumps can be more comfortable

Major environmental benefits aside, a high-performance heat pump legitimately feels like a major upgrade to your heating and cooling system. Here are the upsides:

- They’re fantastic at holding steady temperatures and humidity levels. The secret is that they’re designed to run best at a low level, constantly moving a little bit of air and heat. (Some models have dehumidification-only settings, too.)

- They tend to be quieter than other systems, both indoors and out. This is another upside to the low-and-slow strategy. It’s a huge improvement over window air conditioners or portable air conditioners in this regard.

- They create fewer hot or cold spots. This is because the air is constantly mixing, ever so slightly. And compared to small space heaters that you’d plug into a regular outlet, mini-splits can simply generate much more heat.

- You don’t need to set back your thermostat at night to save energy. You still can, if you’d like. But high-performance heat pumps actually run most efficiently when you leave the thermostat alone.

- They can improve your indoor air quality. This isn’t unique to heat pumps, but HVAC systems that constantly move air—paired with a good filter—do a better job of capturing dust and other floating particles. Consistent humidity control helps, too. And you won’t have to worry about carbon monoxide leaks or byproducts of burning fossil fuels inside your home.

Who gains the most by upgrading?

- Anyone replacing window ACs, plug-in space heaters, or other loud, heavy, underpowered, slightly dangerous gear. Even some of the most basic ductless systems are a huge improvement over room ACs and small heaters. They do cost more than portable equipment, but they’ll save some money on your electric bill and keep you so much more comfortable. And since they’re permanently installed, you won’t have to worry about safety hazards: Dropping the AC out of a second-story window or injuring your back lifting it onto a windowsill, accidentally burning a curtain that’s touching a space heater, and so on.

- Anyone who needs to add heating and cooling to rooms that the primary HVAC system doesn’t reach. Heat pumps are modular and relatively easy to install in spaces like garage workshops, attic hangouts, bonus rooms, home additions, etc. It’s usually easier than extending ductwork or a hydronic system—and again, it’s much more comfortable than the cheaper, non-permanent alternatives like window ACs or space heaters.

- Anyone who finds it annoying when the temperatures swing around throughout the day. Nearly all fossil-fueled and electric-resistance heating systems have this problem. So do most lower-cost central ACs—which can also struggle to keep humidity under control. But high-performance heat pumps have components that let them adjust their output on the fly to blow the just-right amount of warm or cold air to keep your home comfortable.

- A caveat: Basic, single-stage heat pumps act more like traditional HVAC systems. (These are affordable, centrally-ducted systems—common in the southern US.) That’s because they’re either all on, or all off. But it’s the status quo, not a downgrade from a traditional system.

As with any type of HVAC system, some people have a bad experience with heat pumps—leaving their home chilly in the winter, or muggy in the summer, among other problems. But these “problems with heat pumps” usually stem from poorly designed systems, botched installations, or equipment in need of maintenance (or a combination of all of the above).

And there’s always the possibility of an extreme cold-weather event like a polar vortex or arctic blast that pushes a heat pump beyond its limits. Cold-climate heat pumps shouldn’t stop working in cold weather unless the outdoor unit ices up because of a sloppy installation. But they might struggle to keep your house comfortable. It happens! You should think about a contingency plan for these rare events, whether that’s a full backup system, some electric space heaters, or just a bunch of blankets.

Will you save money with a heat pump?

The numbers are a little fuzzy, but at least one-third of households in the US will save money by choosing a heat pump instead of a traditional heating and cooling system. It’s probably more than that—we’d estimate something more like 50 to 60 percent, given prices as of early 2023.

The up-front costs of heat pumps are generally higher than other HVAC systems. But that’s not always true. And heat pumps cost so much less to operate compared to certain kinds of heating systems that they’ll pay for themselves through savings on your utilities. Heat pumps pair very nicely with rooftop solar, too.

The details depend on where you live and what your other options for heating are. But here are the broad strokes:

In warmer climates, basic heat pumps are often the most cost-effective systems from the get-go. That’s because they can cost less than the combined price of a furnace and AC. Plus, they tend to cost less to run than furnaces or electric-resistance heaters in regions where the winter temps are mild. So you win in the short term and the long term. (To cover the occasional cold snap, they’re usually installed with an electric-resistance heat strip, built right into the condenser or air handler.) And if they’re replacing an old, inefficient AC, they’ll trim your cooling bill, too.

Heat pumps cost much less to operate than systems that run on oil, propane, or electric resistance. That’s true even in very cold climates. It’s enough of a discount on your energy bills—often around $1,000 per year, according to the DOE—that the heat pump will almost always offset its higher installation costs, typically within 5 to 10 years. (The industry consensus is that a heat pump should last about 15 years.)

)

Heating with natural gas tends to cost less, particularly in cold climates—but there are tons of exceptions, and it’s not a runaway. Here’s a vast oversimplification: On average, a cold-climate heat pump installation costs about $4,000 more than the combined price of a gas furnace and a central AC, even after rebates for the heat pump. Heat pumps also tend to cost a little bit more to operate than a gas furnace, something in the ballpark of $100 or $200 per year. On paper, with all the nuance sanded away, gas furnaces are a more economical option than heat pumps in cold climates.

But those are just averages. The real-world ranges are huge—there’s a $20,000 difference between the least- and most-expensive cold climate heat pump installations, after accounting for incentives. (The price range for a furnace is much narrower). So there are plenty of cases where heat pumps beat gas on cost. (Some sources even claim that heat pumps usually beat gas, though the industry consensus and real-world data don’t quite support that.)

It’s very much a case-by-case thing, though the more of the following that apply to your situation, the better the case for a heat pump:

- Existing ductwork, or a home that won’t need too many ductless “zones” (more on those later).

- Good local incentives, plus honest installers who pass those savings to their customer instead of jacking up their prices.

- Inexpensive electricity, whether that’s from the grid (like in areas with lots of hydropower), a community solar farm, or rooftop solar.

- Milder winters, so that the heat pumps spend more time running near their higher efficiencies.

- A well-installed heat pump, used in a way that maximizes efficiency (this means no fiddling with the thermostat if you can help it).

Another option to consider: Hybrid systems—heat pumps and gas—can be a best-of-both-worlds option. The heat pump does your cooling and most of your heating. When it gets really cold, your gas system fires up. Think about getting one if you need to replace your central AC, but still have a heating system that works.

Heat pump incentives: How to get free money

As of 2023, many high-efficiency heat pumps qualify for a federal tax credit, and might also qualify for generous rebates or other incentives from state and local governments, as well as utility companies. That includes air-source heat pumps, as well as ground-source systems. There are a lot of details still up in the air, but here’s an overview of what should be coming down the line thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act.

And in the meantime: One of the best sources of information about heat pump rebates is DSIRE, a database managed by the North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center.

What’s a mini split? And other types of heat pumps

There’s a whole HVAC language to describe all the different types of heat pumps and how they work. Here are some of the terms you’ll probably come across in your journey, defined briefly.

Mini-split: It’s basically another name for a high-performance air-source heat pump: More efficient, more flexible, and more comfortable than basic duct-only systems.

There’s some disagreement in the HVAC industry about the precise definition. A lot of people use “mini-split” and “ductless” interchangeably, though that’s not quite right. Here’s a way to think about it: Ductless heat pumps are (almost) always mini-splits. But mini-splits aren’t always ductless; plenty of brands sell ducted systems that they call mini-splits, too. You don’t need to worry too much about the specifics, though. Mini-split is a marketing term more than a technical term.

Ducted heat pumps and ductless heat pumps: This tells you how a heat pump moves conditioned air around your home. They use the same underlying tech to generate warmth or cooling, but they deliver it differently.

Ducted systems, naturally, connect to ductwork through an air handler that usually has a large fan.

In a ductless system, you’ll usually have one air handler (or “head”) per room, attached to the wall or ceiling, and connected to the outdoor unit by a long tube running through a 3-inch hole in the wall.

Air-source heat pumps: The most common type of heat pump, one that relies on the air outside your home as a heat source (or heat sink, in cooling mode). It looks like a central air conditioner and is easy to install in most homes.

Ground-source heat pumps, aka geothermal heat pumps: The other common type of residential heat pump. It relies on hundreds of feet of tubing buried underground in your yard—either in trenches or drilled straight down with special equipment. Below the frost line, ground temps are a stable 50 to 60 degrees all year, and that allows the heat pump to run super efficiently. Ground-source systems are difficult and expensive to install but typically pay for themselves through savings on your energy bills.

Water-source heat pumps: Similar to a ground-source system, except the long tube sits in a body of water (usually a pond or lake).

Air-to-air heat pumps: A type of air-source heat pump that distributes heating and cooling through a forced-air system—either ductwork or with ductless “heads.” The vast majority of heat pumps sold in the US are air-to-air systems.

Air-to-water heat pumps: Air-source heat pumps that distribute heat through hydronic (hot-water) radiator systems. These are the norm in parts of Europe. So in theory you’d be able to get one in the US—but it can be tough to find a qualified installer. They don’t work well with baseboard radiators and aren’t useful for cooling.

Single-zone vs. multi-zone heat pumps: These terms describe the number of air handlers or ductless “heads” connected to one outdoor unit. If it’s a simple one-head, one-compressor system, that’s a single-zone system. If multiple air handlers are connected to a single outdoor compressor, that’s a multi-zone system (sometimes called a multi-split). Single-zone systems are more efficient. But if you need HVAC for multiple rooms (and don’t have ducts), it’s usually more practical to install a ductless multi-zone system. Most multi-zone heat pumps can accommodate up to five heads, though there’s some evidence that it’s better to stick with a maximum of three heads per outdoor unit.

Cold-climate heat pumps: These are heat pumps that can keep your house warm even when it’s cold outside. Basic heat pumps stop working well around 32 F—they can’t generate enough heat to keep up with the amount of heat that your house is leaking. Cold-climate heat pumps can work at much lower temperatures. The closest thing to an “industry standard” for a cold-climate heat pump is to crank out at least 90% as much heat at 5 F as they do at 45 F. But plenty of models keep working well below zero. They still work great in warm weather, too.

Backups, heat strips, hybrid, and dual-fuel systems: Different names for the same basic idea: A secondary heating system that can take over for the heat pump. Unless you live in the very coldest parts of the US (like northern Minnesota or Alaska) or don’t have reliable electricity, a whole-home backup isn’t strictly necessary. But you might want one for peace of mind. And combo systems can be the most economical way to heat your home, whether that’s a simple heat pump plus an electric-resistance heat strip, or a hybrid (aka dual-fuel) system that switches to gas heat when the temperature drops below a certain threshold.

Single-stage vs. variable-speed compressors: This is the dividing line between “basic” and “high-performance” heat pumps. Single-stage systems can only be on or off; it’s either the full amount of heating and cooling, or nothing. This can work fine in warmer climates, and the equipment costs less. Heat pumps with variable-speed compressors cost more but work better and save energy. They can adjust their heating and cooling on a scale—sometimes in dozens of steps. Variable-speed systems are necessary for cold-climate heat pumps, but also help with cooling, because they’re better at controlling humidity. Inverter-driven is another common term that means basically the same thing as variable-speed, in this context.

For the rest of this guide, we’ll be focusing primarily on air-to-air heat pumps.

What are the best heat pumps?

Don’t get too fixated on this.

On paper, there are plenty of great heat pumps. There are sure to be at least a handful of models that will work well in your home and meet your heating and cooling goals (with a couple of caveats).

Even if you identify what you think is the perfect heat pump, it might not be available when you want to install it. There’s been a supply crunch for heat pumps lately, given the huge spike in demand, and ongoing logistical problems with the worldwide supply chain.

Or the installer you like could have a line on an equally or almost-as-good option for a much better price. Or they might prefer to work with a different brand and will offer a better warranty for that equipment. (It’s much more important to have a great installer and a well-designed HVAC system than to have the very best heat pump.)

But before you talk to an installer, it helps to have a handle on what makes a heat pump a good fit for your home and local climate.

Which heat pumps work well in the cold?

Any heat pump can work well on hot summer days or mildly chilly days. But once the temperature drops below freezing (32 F), some models can’t hack it. Fewer still can work down into the single digits. And only a select group is reliable at temps well below 0 F. Most installers will pick the correct equipment for your environment, but it’s not a guarantee. If you want to double-check your installer’s recommendation, first look up your climate zone, and then figure out which “tier” of cold-weather performance the heat pump falls into.

Very Cold

Heat pumps with excellent performance even in extremely low temperatures, below 0 F.

If you live in:

- Climate zones 1-3: These heat pumps are overkill. You don’t need such a high-performance heat pump if you live here.

- Climate zones 4-5: The “peace of mind” pick. It rarely gets cold enough where you live to need their full heating capabilities. But it won’t hurt to have it, especially if you won’t keep a backup system.

- Climate zone 6: A fantastic fit for your weather.

- Climate zone 7-8: These heat pumps should be able to handle the vast majority of your heating, though there are likely to be some days when a traditional furnace would come in handy.

Heat pumps in the Very Cold tier include:

- Mitsubishi H2i Hyper-Heat

- Daikin Aurora

- Fujitsu Airstage / Halcyon XLTH

- LG Red (except the central ducted unit)

- Carrier Infinity 38VM

- Samsung Max Heat

Cold

Heat pumps that work near-flawlessly down to about 5 F, and can still churn out some heat in colder temps.

If you live in:

- Climate zones 1-2: These are overkill.

- Climate zones 3-4: A great fit for your weather; it’s extremely unlikely you’ll need a backup heating system in these regions.

- Climate zones 5-6: Also a great fit, though you might need a backup source of heat from time to time.

- Climate zone 7: One of these could make sense as part of a hybrid system, where you’d expect to run a traditional furnace or boiler during the coldest weeks of the year.

- Climate zone 8: You’ll probably want to upgrade to a model that’s better suited for very cold weather.

Heat pumps in the Cold tier include:

- Bosch Climate 5000 Max Performance

- Mitsubishi M Series and P Series without H2i

- LG Red central ducted unit

- LG: Most non-Red models (except Mega and Standard Efficiency)

- Fujitsu: Most other Airstage / Halcyon mini-splits (except entry-tier models)

- Fujitsu FO*20 ducted

- Daikin MXS and RMXS

- Carrier: Most Infinity models (except 38VM)

- Carrier Performance 38MG

- Lennox Signature SL25XPV ducted

- Lennox MLA and MLB mini splits

- Rheem Prestige RP20

- Samsung: Other models besides Max Heat

- Mr. Cool Universal and Olympus Hyper Heat

Mixed climate / In-betweeners

These models can work well down to around 15 F or 20 F.

If you live in:

- Climate zone 1-3: A fantastic option, able to carry you through the winter likely without having to switch to a backup heat strip (outside of unusual cold snaps). And since they have variable-speed compressors, they’ll keep your home more comfortable than basic heat pumps during the summer as well.

- Climate zone 4-7: They can make sense as part of a hybrid system where you’d expect a backup to run at least a couple of weeks per winter, though some models are a better fit than others.

- Climate zone 8: You probably want to look elsewhere.

These heat pumps include:

- Bosch Climate 5000 (non-Max Performance)

- Bosch ducted systems

- Fujitsu: Entry-tier Halycon / Airstage mini-splits

- Fujitsu FO*16 ducted

- Daikin: Other mini-splits, including Fit and VRV systems

- Daikin: Most ducted systems with SEER rating 16 and above

- Trane: Most ducted systems with SEER rating 16 and above

- Lennox: Most ducted systems with SEER rating 16 and above

- Lennox MPC, MHB, and MPB mini-splits

- Rheem: Most ducted systems with SEER rating 16 and above

- Mr. Cool DIY, Olympus, and Advantage series

- Goodman: GVZC20

Warm

These are basic heat pumps that work well down to about 32 F. They’ll spend more time in cooling mode than in heating mode.

If you live in:

- Climate zones 1-3: A solid, budget-friendly option for whole-house HVAC. They’re typically installed with a backup heat strip, and it might turn on sometimes.

- Climate zone 4: They can make sense as part of a hybrid system, paired with a gas furnace.

- Climate zones 5-8: You’re probably better off with a different heat pump.

Dozens of heat pumps fall into this category, and they’re all centrally ducted units (not mini-splits). If the SEER rating is below 16, it’s a warm-weather model.

Ducted versus ductless heat pumps

Most heat pumps are installed with one or both of the two most common types of air handlers:

- A big, traditional air handler serving central ductwork in your home—what most people call a ducted heat pump.

- One or more wall-mounted “heads”—those boxy units that people tend to picture when they think of ductless heat pumps.

All the best heat pumps come in both of those varieties. But most brands offer a handful of other types of air handler that can work with their higher-performance mini-split heat pumps:

- Slim duct or compact ducted units sit inside ductwork. They’re designed for short runs of ductwork that serve a few rooms—not central ductwork that serves an entire house (their fans are too weak).

- Ceiling cassettes are ductless heads, but mounted inside your ceiling rather than on a wall. They tend to cost more and run less efficiently than the wall units, but they’re concealed—they aren’t so ugly, basically. Installation isn’t always feasible, especially if floor joists are in the way.

- Floor consoles are ductless heads that are mounted low on a wall. They can make sense in rooms with slanted ceilings, or when they’re replacing radiators.

- “Designer” heads are just spiffed-up versions of wall, ceiling, and floor units. A lot of people think ductless heads are ugly, but what if they get a nicer finish and sleeker design? LG even has a line of heads that double as picture frames.

Other important heat pump specs

Controls

Centrally ducted units connect to a central thermostat like traditional HVAC systems do.

Ductless systems—by default—are controlled with a basic remote control for each individual indoor head. But there are ways to tie them together into a centralized (or zoned) system.

In heat pumps with variable-speed compressors, you should expect to use the manufacturer’s thermostat—not a third-party thermostat, even a seemingly advanced, “smart” model like the Google Nest or Ecobee. Clever as they are, those thermostats don’t regulate the heat pump’s compressor for maximum comfort or efficiency.

Efficiency

The industry-standard specs to measure efficiency are (as of 2023) SEER2 for cooling and HSPF2 for heating. This topic is painfully dry, so we’ll leave the nuances for another article. But the general idea is that higher numbers mean less energy use. Systems with higher SEER and HSPF ratings tend to cost more but might pay for themselves through energy savings, and are more likely to qualify for incentives and rebates.

If you live in a warmer climate, where the heat pump spends more time cooling, focus more on a higher SEER. If you live in a colder climate, a higher HSPF is more important. The two specs tend to be correlated anyway, but there are some exceptions.

Another efficiency spec you might hear about: Coefficient of performance, or COP. This is a direct measurement of how your heat pump is actually working—that is, how much heat (or cooling) you get for the amount of electricity consumed. Your seasonal COP will depend on how well-designed and well-installed your heat pump is, and how close you hew to the best practices for using your heat pump.

Reliability and warranty

As with any major household purchase, reliability is the big question—and nobody has a good answer yet. Consumer Reports publishes some reliability data, but it mainly covers ducted systems, and the lion’s share of its data comes from warm-weather states. They don’t have ratings for major mini-split brands like Fujitsu, Daikin, or LG.

Some brands have slightly better warranties than others, but they’re all in a similar wheelhouse: They’ll cover some or all of the parts for 5, 7, or maybe 10 years. If you get the equipment installed by a preferred contractor, sometimes that extends out to 12 years. But you’re always on the hook for labor costs. (Some contractors might offer labor warranties, though.) A longer parts warranty certainly won’t hurt, but don’t put too much stock into these numbers, even into differences of several years.

How to get a heat pump installed

A good installation is the key to a great experience with a heat pump. Yes, you need the right equipment for the right house and the right climate. But a bad installation of even the best equipment can lead to sub-optimal efficiency, poor performance in cold weather, and reliability problems down the line.

Pick someone who has experience with heat pumps, or at least air conditioners, rather than someone who has until recently focused on furnaces or boilers. Heat pump specialists are much easier to find in warmer parts of the country—but the market is expanding rapidly.

Some systems are geared toward self-installation—that is, they come with pre-charged refrigerant lines, so you don’t need a whole bag full of HVAC specialty tools. But there are still tons of ways you can botch the job. Proceed with caution!

What to expect when you work with an installer

When you first contact an HVAC contractor, they might be able to give you a general idea of what a heat pump installation could cost without visiting your home, if you can provide accurate details. But this is uncommon, and the huge majority of contractors will need to make a site visit.

Site visits usually go like this:

- You schedule an appointment through the installer’s website, or over the phone. If it’s an emergency—your system dies during a cold snap—you can usually find a contractor who will arrive on the same day.

- When the contractor arrives, they’ll almost always start by having a conversation about your expectations. Some companies send a project consultant rather than an actual installer—somebody who has enough training to give you a quote but doesn’t perform the actual work. That’s OK, this is a common practice.

- Then you’ll do a walkthrough of your property with the contractor.

- They’ll want to see your existing heating system and any ducts you’ve got in place.

- They’ll also be looking for places to fit all the new equipment: The outdoor unit, the indoor air handlers, and the lines that connect the two parts.

- They’ll also check out your electrical panel, to make sure it can support a heat pump.

- They (should) take some measurements along the way—room sizes, duct sizes, that kind of thing. Most installers will not measure existing insulation, or perform a blower-door test to find out how leaky your home is. You’ll usually need a separate energy audit if you want to find out the ideal capacity for your heat pump.

- Most contractors try to design a good-enough system and give you a quote on the spot, but some will head back to their office and follow up with a quote later.

Do you need other home upgrades before you get a heat pump?

Usually not. Sometimes they’re necessary—like if your electrical panel doesn’t have enough open slots for a new circuit.

Other times, upgrades aren’t required but would be a really good idea. Insulation and air sealing are common points of improvement, and your ductwork might need some maintenance. If your home feels drafty in spots, or some rooms don’t get as much heating or cooling from your ducts as they ought to, a heat pump won’t magically fix those problems.

Some incentives and rebates are contingent on improving your home’s weather sealing, though generally, you can perform those upgrades after the heat pump has been installed.

Heat pump maintenance

The main step you can take to keep your heat pump performing at its peak potential is to keep the filters clean. This keeps the air flowing properly, which means better comfort and better efficiency. The right cadence depends on your particular system.

Beyond good filter hygiene, heat pumps are supposed to have professional maintenance once a year, though you can probably get away with longer intervals. Different pros have different takes on what’s necessary and what’s useful—there’s not an industry consensus. Some insist that you should check refrigerant levels every year, while others say that this step just increases the chances of a leak later. Some suggest cleaning the drip pan and coils annually, others say just clean them as necessary.

For what it’s worth, Consumer Reports found no correlation between regular maintenance and long-term reliability. But it’s probably unwise to put it off for too long. And whenever you notice the heating or cooling performance beginning to suffer, call a pro because you might have a refrigerant leak.

Often, contractors will offer a maintenance package that includes an annual service for a fee. If you’re considering this, it’s worth asking about other perks, like whether having a maintenance contract will give you priority in case of an emergency. Some installers will offer fast-service guarantees for contract holders, and that could be worth it for peace of mind alone

Text taken from: https://www.energysage.com